Speaking of the Dead

by Chris Vrountas

I am a grandson of immigrants from what some might have called a “shithole country.” My grandparents were poor, from poor villages, from a poor part of the world. They were not just data points wrapped in olive skin speaking a foreign language and cooking funny smelling food. They were husbands and wives, fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, laborers and artists, lovers and mourners, leaders and failures, fighters and dreamers. They were people, like all other people. Yet, like immigrants today, my family and others similarly situated were viewed upon their arrival in the US by some American leaders as “new immigrants” who threatened to make “a great and perilous change in the very fabric of our race,” as Henry Cabot Lodge, the Senator from my home state, once wrote over 100 years ago. Sadly, very little has changed.

My immigrant grandparents are all dead now. But they continue to whisper to me. They tell me to open my eyes and open my heart. Listening to their whispers, I see the new arrivals at the southern border through their eyes. I see the threat to suspend habeas corpus through their eyes. I see the denial of personhood and citizenship guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment through their eyes. I see the pretextual complaint about “illegal immigration” through their eyes while their descendants demand changes to laws to keep new immigrants out of the country immigrants built. Looking through their eyes, I share their terror at seeing immigrants who have committed no crimes taken off the street in surprise arrests.

When my family first arrived in the US, they did not look so different from those being arrested today. It is deeply disappointing to hear the language that the descendants of immigrants use when talking about today’s migrants, people who just want the same chance to work for a better life. So many of these descendants, while they mostly identify as Christian, ignore the biblical injunction to “neither mistreat a stranger, nor oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” Perhaps all non-indigenous Americans need to be reminded of their own immigrant story. Perhaps once they remember their common humanity, they will look upon contemporary migrants with understanding and compassion rather than fear and hypocrisy. As my late grandmother used to say, “You’re not the first, and you won’t be the last.”

Visiting My Immigrant Past

Uncle Bill had been dying for years. He was one of the few family members left from his generation, the first wave of our family that came to this country near the turn of the century from Greece. On news that his health was failing, my mother called me. “Go see him while you have the chance,” she said.

He was ninety-six years old at the time and he came from another world. I was just out of school. He lived in a row house on a postage stamp lawn behind a chain link fence with my aunt Zoe. She was a spry eighty-seven and she opened the door with a young smile, hugged me with energy, and ushered me down the narrow hallway to the front parlor. Bill Loupos sat in his stuffed chair by the window, his walker beside him and his spit bag by his feet. His pajamas and bathrobe hung off his frame and his thin hair waved over his balding head. His chiseled face looked up as I entered the room. While he had supposedly declined, he looked no different than he had the for the last twenty years I had known him. To me, he was always old.

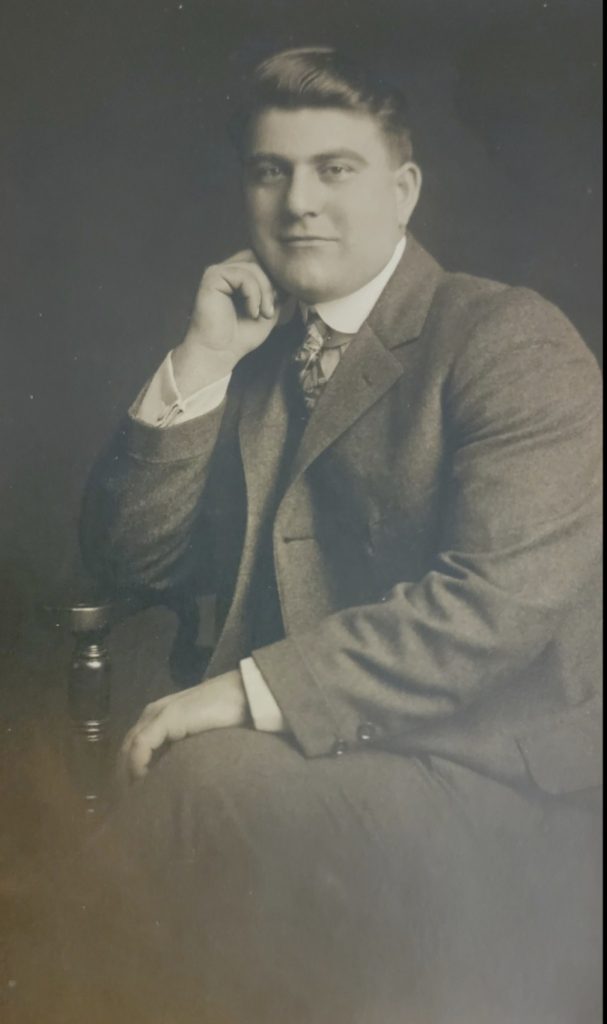

But he wasn’t always old. The sepia-toned photograph in the water-stained paper frame on the bureau in my office tells me so: jet black hair, piercing dark eyes, pronounced jaw framing his beefy face. His whole body leans back on the studio chair as he sits cross-legged wearing a gray suit, spats, crisp white collared shirt and a silk tie as he stares down the future that might dare oppose him when that photo flashed at least 100 years ago.

I sat on the couch across from Uncle Bill’s chair and Zoe offered me a ginger ale like she did when I was a boy visiting with my parents. I took in this room that always held an air of formality. We didn’t visit often. There was no playing here. Bill and Zoe had no children, and the house had the delicate orderliness of a place that was not used to kids. The parlor was heavily decorated with artifacts from their era, including dark wood end tables covered with white lace.

I didn’t know a lot about my uncle Bill. I knew he left his home in Bambakou, a small mountain village in the Peloponnese, when he was just a boy to come to this country. He came with his brother Nick, who I never met, and my grandfather, Harry, who I barely remembered. Bill was the only one left, my only direct link to those early days when they first came over.

After the obligatory discussion mourning another Red Sox season, I asked him if he missed Greece or if he ever wanted to go back.

“No!” he said emphatically. “In Greece, I didn’t have shoes on my feet! America is the greatest country on earth!”

Zoe interrupted, “Oh yes you did have shoes on your feet.” She clucked at his exaggeration. “Life was hard, but you had shoes on your feet.”

I asked Zoe what she thought when she first arrived in America. She recalled standing at the railing on the ship steaming into a cold, gray, and foggy New York Harbor. Dark, monstrous buildings of steel and concrete walled the water’s edge. New York’s sky hung thick and dirty like an old woolen blanket, and the air was soupy with mist and grime, slapping her face with an offensive wet wind. Between her and her brave new world spread the deep ponderous and impenetrable water of the harbor, bulging and hissing like gray molten rock. Even the Statue of Liberty, the mammoth symbol of promise to strangers in a strange land, loomed gargantuan and gray, implacably presiding over the driven herds of cold, huddled, immigrant masses. Zoe, the young woman from the small mountain village of Aghios Petros, could not accept it. She began to cry.

Bill had no romantic sentiments of the Old Country, and Zoe had no illusions about America. They told stories that challenged my very simplistic view of the immigrant story. And they added life to legends that had seemed so distant to me. I learned about the group of boys, teenagers and younger, who lived in a North End tenement on their own, selling bananas from fruit carts each one walked eleven miles a day from Haymarket Square to Arlington to retrieve. Their pay was pennies for commission and all the rotten fruit they could eat when the sun went down. Tuberculosis and the broken window in their room winnowed the group’s number during the winter. I learned how a young family survived the Great Depression, and how they endured a father’s death and a failed business. There were stories about love, betrayal, war, murder, death, resurrection, triumph, and loss.

Zoe kissed me at the door after my visit and told me, “Don’t become cold, like a cucumber.” I shrugged and joked, “I like cucumber.” She said, “It’s nice, in a salad. But it’s cold. They are cold. Don’t be cold, like cucumber.” I thought she was warning me about dating my girlfriend, a girl from New Jersey who was not Greek and who might not fit into our family.

I stepped away, annoyed at her comment. Who was she to say? Her house was so warm? When we visited when I was a boy, there was no playing, no ball outside, no games inside. Just everything in its place. We sat properly on the laced couch, accepting the ginger ale and koulouria offered by my great aunt.

But as I look back, she was not concerned about my girlfriend. She was concerned about my generation. “Don’t become cold, like cucumber.” The warning still whispers. Is that what we have become? Now, three generations in this country, have we become “cold like cucumber” to people like us who want a better life? Have we failed our immigrant stories? Have we lost our humanity?

We’re No Better Now

It has become common to see people who once spoke proudly of their immigrant heritage demonize new arrivals who possess the same dreams and ambitions their ancestors did. Immigration has always been controversial, but it startles me how we as a people have not evolved. Americans still talk about “immigrants” as if they are a “problem,” and we forget our origins when we do. We rage against foreigners while eating our Italian pizza and our Greek salad prepared by new immigrant hands from Venezuela or the Dominican Republic. We fail to realize that the change we resist will become the delicious normal in the future. An entire leadership class has shed its belief in Ronald Reagan’s vision of America as special because “anybody can be an American” and because “we draw our people … from every country and every corner of the world” so as to “continuously renew and enrich our nation.” Even Senator, now Secretary, Marco Rubio, who not long ago exhorted America “not to give in to the fear” and to remember that “[w]e are the descendants of immigrants and exiles,” now adopts the atavistic politics of fear by following the current chief executive who argues that immigrants “are poisoning the blood of our country,” or that they “come from shithole countries,” and that such countries are “not sending their best,” that new arrivals have come as an “invasion,” and that they are bringing their “problems” as if America has ever been anything but a tumultuous salad bowl of nations. There was no perfect American moment in the past. No one was any better in the old days. And, sadly, we’re no better now.

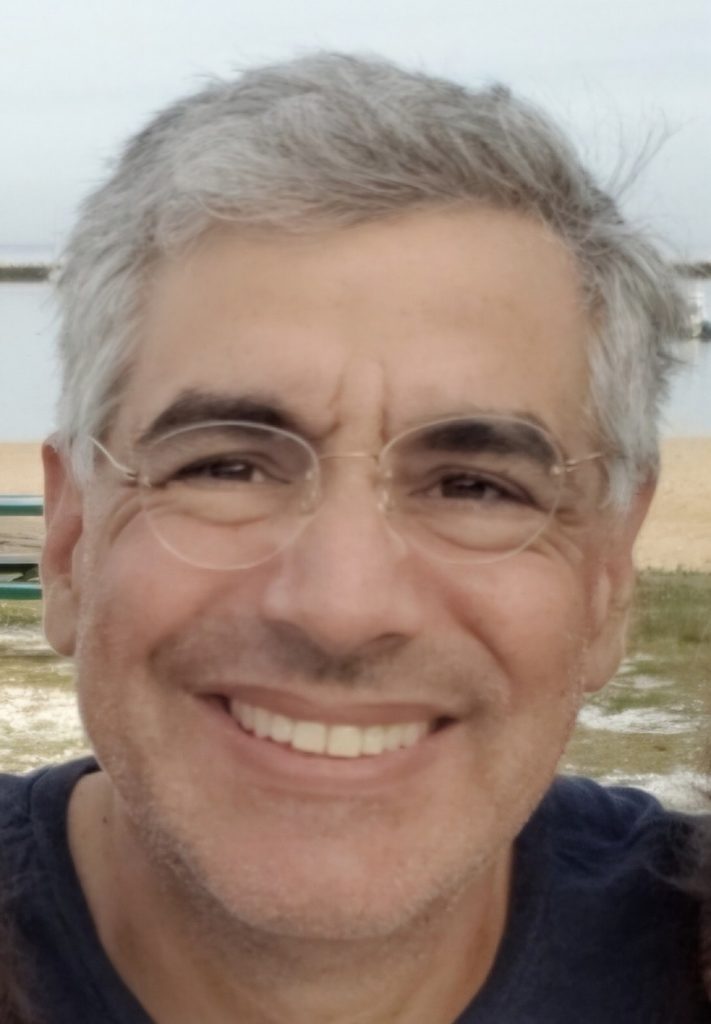

If we could only speak to the dead, perhaps they would talk some sense into us. Their stories might snap us out of our fear. Their names that once sounded foreign and their DNA that made them look different when they arrived have been passed down to us. All we need to do is look in the mirror. When I do, I see my father’s lines in my face and my grandfather’s eyes looking back to me, and I consider how the stern look that is returned to me masks the stories behind who I am and how I got here. I can faintly make out the grandfather I never met, the man who doted on his two young daughters and felt such pride in his son and loved his wife dearly, a man who died younger than I am now. I see my grandmother who was not just the laconic and dissatisfied woman she appeared to me when I was young, but a young and beautiful striver who married and crossed an ocean to fulfill aspirations she held. Looking in the mirror, I can feel the sting my grandfather felt when the real estate agent wouldn’t show him a house because there were “too many Greeks” in the neighborhood. I can feel the pit in my mother’s stomach when she arrived in first grade without knowing any English and her self-consciousness at having only one dress to wear to school. The taunts from the other children will never leave her, but neither will the kindness of the one teacher who took the extra time to teach her English.

Lessons from the Dead

Uncle Bill was not just the haggard old man in pajamas who sat all day in his stuffed chair. He was the man who, among other things, worked at his diner for forty years, sold it, invested everything he had, and lost it all in the stock market. Instead of giving up, that shrewd, hard-nosed fighter literally doubled down and invested all he had left “on margin.” The investment exploded and made him rich, but he never moved from his little house in Arlington. Within weeks of my visit, Bill Loupos died and left millions to stunned and thankful friends. The shoeless boy from Greece had given away a fortune.

What other treasures did our immigrant ancestors leave for us? Perhaps their example not to be afraid. People fear immigration because they fear change. They mistakenly believe that change means loss. With immigration the faces around us change, and we add new customs and new traditions, new flavors in the salad, but those new faces also bring renewal. With new influences and new aspirational energy, the whole of us grows.

I remember taking a picture of my girls when they were little, racing each other on the lawn with their arms wide like airplane wings, soaring in the total freedom that only children know. I wanted that time to never end. I still have the old photo, but they’ve flown now, grown into the fullness of themselves. Do we focus on loss or on growth? That change is constant is an eternal truth. We need not fear change but see that life’s impermanence makes it beautiful and the potential for rebirth brings new hope.

I married the girlfriend I thought my aunt warned me about. Good thing I did. Yes, marrying her meant change, and we built our own lives and did things differently than our ancestors did, just as our ancestors broke away on their own. The immigrant experience is a metaphor for life. We all must leave something or some place to move on to the next part of our lives. Some leave their country, others their hometown or family, some leave school or their old job, or even their youth to move on to later life stages. We all arguably are new arrivals on this planet, and we all eventually will need to leave it. As migrant souls in this vast universe, surely we could identify with and learn something from the immigrant experience.

This is not an argument for disorder at the border. It’s just an argument for respect and compassion over fear and hypocrisy. Is it so hard to treat people fairly? To give people notice and an opportunity to be heard? To respect migrants as people as you would want your own grandparents respected? In doing so, we can remember where we came from and perhaps see the common humanity in others with some humility. In the process, we can be grateful for the continuing and evolving feast at our truly American table, filled with old favorites and delicious new recipes, nourishing all of us.

Chris Vrountas is a lawyer and writer. He lives in Essex County, Massachusetts with his wife, who still laughs at his jokes after thirty-five years. He serves as a mediator of discrimination disputes for the Human Rights Commission. He grew up in an immigrant faith tradition that has evolved over the years, and he writes about impermanence, hope, and rebirth.

If you appreciate the work that you read at bioStories, please consider donating to help us continue to bring you voices of such quality and originality.